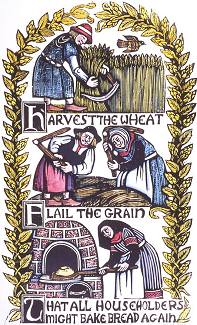

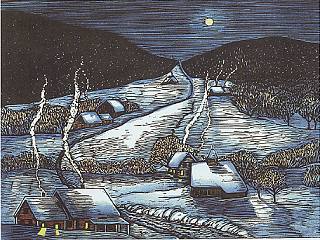

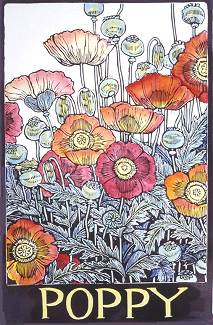

Mary is a tall woman in her mid-fifties, with long graying hair pulled back and fastened in a utilitarian twist. With strangers she can seem intimidatingly confident or, adopting the flat Virginia smile she learned as a good little girl, blandly polite. With friends, though, she is funny, generous, and richly opinionated. She is well-read and well-informed and integrates gracefully what appear to be strange contradictions: Her politics are progressive, but she watches football; she is anti-consumerist, but indulges gleefully in a little retail therapy and makes her living from selling; she is not particularly competitive or ambitious in her work, but is a cutthroat bridge player. Throughout, she retains a certain remoteness, drawing a careful line around her emotional privacy. In fellow Vermonter Snowflake Bentley--who died in 1931, a decade before Mary was born--she has found an uncannily good match for her ethical and artistic values. A passionate yet practical eccentric, Wilson A. Bentley found his life's work in studying and photographing the uniqueness, symmetry, and beauty of single snowflakes. Neither selfish nor selfless, he simply devoted his days to work he loved: capturing the transient elegance of a snow crystal. But Bentley was no self-indulgent artist; he was a competent farmer who did not ignore the practical necessities of survival. He also published his work in academic journals and promoted sales of the photographs he made. Mary has much in common with this craftsman farmer. In her own way, she is somewhat of an eccentric. She adheres to her own path, which sometimes conforms, and sometimes does not, to conventionality and fashion. A back-to-the-lander in the early 1960s, she and her husband, Tom, moved to Cabot, Vermont, and embraced the state's virtues-both mythic and real. They raised three sons and much of their own food, and their daily lives reflected the tasks and turnings of the seasons. In her first years in Cabot, Mary was a teacher, but as her family grew, she tried to figure out a way to stay at home. Soon she turned her woodcarving skills into a small income and then a small business. That evolution coincided with the craft boom of the late sixties and early seventies that an invasion of city-weary hippies had brought with them to the Vermont countryside. As that tumult swirled around her, Mary worked. She honed her skills; kept her family in wood, taxes, and car repairs; laid the best table for miles around; maintained an independence of thought and vision; and tried to carve out a good life. She also carved out a good number of increasingly fluent woodblocks. The posters she began printing and painting by the hundreds and then thousands reflected the Vermont values of home and hearth and celebrated the beauty of garden and landscape in a way that was nostalgic without being sappy, personal with being self-referential. (She also contributed biting political posters opposing U.S. intervention in Central America and donated graphics to scores of organizations promoting social and economic justice.) And the prints sold, at small craft fairs and local shops. Some of her neighbors shook their heads. "Seven dollars," noted one, with a gasp of wonder and a touch of irritation, "for a piece of paper." Well, a little more than just a piece of paper. The craft of woodblock printing goes back to the Middle Ages. Mary, who incorporates Japanese and European techniques, starts with a fine-grained board. She sketches a fairly detailed design on the board in dark ink and then covers the whole surface with a light wash of color. Using razor sharp U- and V-shaped gouges of varying degrees of fineness, she carves away the wood around the black lines to expose again the light wood color beneath. When the process is finished, the lines of the sketch remain as a raised surface. When Ann Rider, an editor at Houghton Mifflin, read Jacqueline Martin's text for Snowflake Bentley, she knew that Mary's style would be a fine match. The choice was perhaps even more fortunate than Rider knew. Not only was there a sympathy of geography and temperament between Mary and Wilson Bentley, but there was a historical precedent for using woodblocks to capture snowflakes. The first observer who tried to record the stark beauty of snow crystals did so in woodcuts. The crude representations were published in 1553 in Rome, in a book by Olaus Magnus, bishop of Uppsala. Like Bentley's workshop, Mary's current studio in Calais, Vermont, looks out on snow for much of the year. In a good winter, the windows frame white fields spread wide in the pale light; in a bad winter, they expose the gray bones of the land and the threat of global warming. (Don't get her started!) Summer reveals another world, a soft land of green fields and flower and vegetable gardens carefully arranged for color, light, and season, but appearing lushly overgrown and randomly extravagant to the untutored eye. But unlike Bentley's necessarily frigid room, Mary's workshop is warm. It fills a large, well-windowed room on the second floor of her old farmhouse. A new Macintosh computer and a nineteenth-century press sit side by side. The fax machine shares space with a fat, good-natured tabby and crusty palettes of paint. On a stool facing the outside view, Mary carves and paints the prints. Her quick, sure strokes have the rhythm of scything, the sureness of surgery. True to the cliche of competence, she makes it look easy as she strips away all that is extraneous and leaves behind what is vital, what gives meaning. It is not a bad metaphor for the ideal of living that drew her to Vermont and still shapes her life. The next step is printing the block. Mary squeezes a worm of viscous black ink onto a large tray. Working with a speed and determination that appears angry in its intensity, she uses a breyer, a soft rubber cylinder on a handle, to roll the ink back and forth until it is smoothly spread. Once the ink is the proper consistency, Mary rolls the breyer over the surface of the carved block, places it ink-side up onto the bed of the press, and lays a sheet of paper squarely over the block. Her old Van der Cook proof press is a heavy cast-iron contraption that requires considerable strength to manipulate. Using a large wheel, like the pilot's wheel in a ship, she turns a heavy iron cylinder so that it rolls firmly from one end of the block to the other. Under the weight of the roller, the inked uncarved portions of the wood print black, while those areas chipped away by the gouges do not make contact with the paper and remain white. She then repeats the process with a fresh sheet of paper, sometimes for hours at a time. After the black ink has dried, Mary paints around the lines with acrylic paint, watered down to rich translucency. Taking a pile of black and white prints, she applies the same color on each of them in turn and then adds another color: all the blue skies, for example, on each print, then the green leaves, then the red blossoms. Like a river boat gambler dealing aces, she flips the wet prints around the room until all available surfaces are covered. By now, Mary's hands and nails are stained; her apron and jeans are lined with black finger marks and wipe streaks from color-charged brushes. Whether she is producing multiple prints from a carving or one-of-a-kind illustrations for books such as Snowflake Bentley, the process and care she brings to her craft remain the same. Woodblock printing is a mass-production process from a pre-industrial age that marries a mindless rhythm with a mindful aesthetic. And like the flowers from which she draws inspiration, all the prints look the same until you look closely and realize each one has the kind of subtle variation Bentley found within his snowflakes. And each embodies the pleasure and sweat of good work well done. |

| http://maryazarian.com |

|

| . |

|

| . |

|

| . |

|

|

| . |

L

L