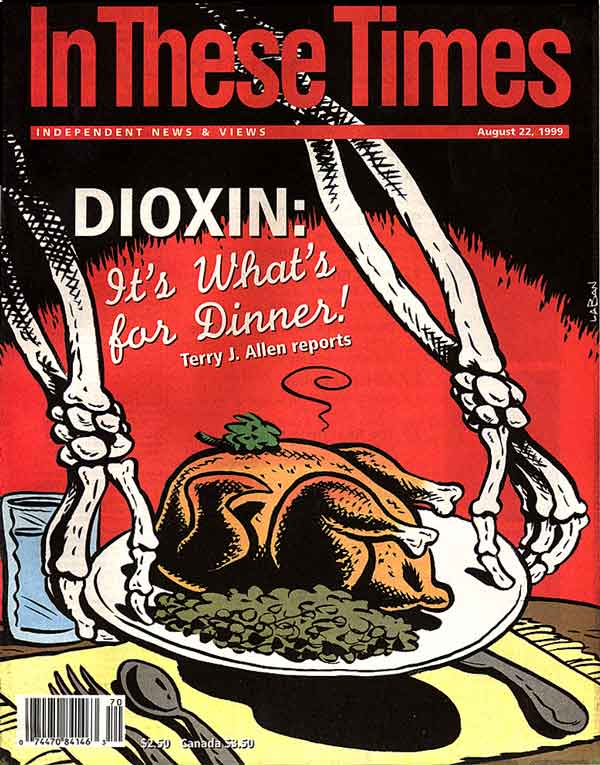

Dioxin: It's What's for Dinner!

Between mid-January and the end of May, hundreds of tons of food -- potentially contaminated with dioxin and PCBs -- entered the United States from Europe. Some already has been eaten, some still sits on shelves in stores and pantries.

The problem started in January in Belgium when a small fat-rendering company incorporated dioxin- and PCB-laced oil into its recycled fat. Eighty tons of poisoned fat then was sold to at least a dozen animal feed companies, most in Belgium, but at least one each in France and Holland. Like ink dropped in a glass of water, the 1,800 tons of animal feed they manufactured spread around the world through vast corporate food chains and complex international trade networks.

| Just one of the contaminated eggs could increase a 3-year-old child's dioxin load by 20 percent. |

It took Belgian officials until March -- when a startlingly high number of chickens started mysteriously dropping dead -- to discover the contamination. After tracing the problem to the dioxin-laced fat, the government sat on the information until May 27 before going public. By then it was far too late to contain the economic, political and public health disaster. Belgian farmers lost more than a half-billion dollars; the ruling party lost the June election; and an unknowable number of reproductive and nervous system problems and cancers were spawned. During the four months between contamination and disclosure, livestock had eaten the feed, stored the dioxin in their body fat, and passed it on in milk, eggs and meat to humans and other animals. Some food contained almost 1,000 times the U.S. limit for the cumulative poison; just one of the contaminated eggs could increase a 3-year-old child's dioxin load by 20 percent.

Dioxin and PCBs are dangerous toxic chemicals and potent carcinogens that pose a serious public health threat. It takes 20,000 times less dioxin than DDT to kill a person outright. But the real danger is that dioxin and PCBs accumulate in body fat over a lifetime and are passed on to fetuses in the womb and to babies through breast milk. The French ministry of the environment estimated last year that as many as 5,200 French people die each year from cancer caused by dioxins. Even low does are dangerous according to a 1994 Environmental Protection Agency report, which found no "safe" level. "The levels of dioxins needed to cause cancer," says Martin van den Berg, a member of a World Health Organization advisory panel, "are a hundred to a thousand times higher than the levels that cause cognitive and hormonal damage."

As the extent of the problem became apparent, Belgium recalled up to 800 products, shut down 1,400 farms and issued directives that affected approximately 100,000 businesses. France identified 103 of its farms that could have purchased the tainted feed. Around the world, dozens of countries acted within days to ban potentially contaminated meat and dairy products. In most of Europe -- and in nations as far away as Malaysia, Thailand, South Korea, Cyprus and New Zealand -- pork, poultry and beef products, Belgian chocolates rich with cream centers, mayonnaise, ice cream, egg pastas, cookies and cakes made with butter or cream disappeared from stores. European Union nations -- as well as countries as far-flung and little-known for their consumer protection policies as China, Russia, the Philippines, Jordan, Indonesia and Kenya -- not only embargoed suspected foods, but sought out and seized items already in circulation.

| Officials estimated that hundreds of tons of potentially contaminated products, from kitty snacks to dairy cow starter, entered the United States |

The U.S. response was marked with inconsistencies. The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates all food except meat and poultry, waited until June 11 to put a hold on animal feed from the EU and egg products from Belgium, Holland and France; on June 23, it embargoed Belgian dairy products. Officials at the Center for Veterinary Medicine were astonished to discover the amount of animal feed that was either imported from, manufactured in, or incorporated ingredients from Europe. They estimated that hundreds of tons of potentially contaminated products, from kitty snacks to dairy cow starter, entered the United States during the four-month window and admitted they had no way to trace batches back to manufacturers.

But the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees meat and poultry, acted quickly with one of the world's stiffest bans. On June 4, it issued a total hold on all EU meat and poultry, even going so far as to ban aged hams produced well before the contamination took place. The USDA's apparently zealous concern for consumer safety was undercut by the conspicuous lack of a recall or consumer warnings. It neither withdrew nor tested any of the 10 million pounds of pork from Belgium, Holland and France; 141,000 pounds of poultry from France; tons of eggs and egg-containing products; as well as the hundreds of tons of animal feed that entered the country between the January accident and June embargo.

Explaining the double standard, USDA spokeswoman Beth Gaston noted: "A ban is based on potential [to cause harm]. But we would only order a recall based on data. We don't have data." But one reason the United States lacked the data was that -- unlike Russia or Tunisia, for example -- it waited for weeks to begin tests. It was mid-June before either agency began tests on products at ports of entry; the FDA has tested some products in stores, the USDA has not. Thus far, no significant levels of dioxin have been documented.

| One USDA employee acknowledges that public health was not the only consideration in determining policy |

The inconsistent U.S. response -- the broad embargo paired with an absence of recall or even in-country product testing -- has sparked speculation about hidden motives. As The Des Moines Register put it, "The Belgian food scare is a perfect opportunity for the U.S. to hit back at the European Union's ban on imports of hormone-treated beef."

Speaking on condition of anonymity, one USDA employee acknowledges that public health was not the only consideration in determining policy. "There is the whole international trade thing, [the recent trade wars over] bananas, pork, beef. . . . Any of these international issues could be coming into play."

In play at the time was Europe's ban on U.S. beef and restrictions and labeling laws of various EU countries on genetically modified organisms. While Americans have grown used to factory farming and centralized agribusiness, the concept is relatively new to Europe, which still has a strong tradition of small family farms and high-quality, locally grown seasonal produce.

Since 1996, though, Europe has had a crash course in the dangers of industrializing food production. That year, the European Commission banned exports of British beef after strong evidence emerged showing that mad cow disease could infect humans. The brain illness in cattle -- bovine spongiform encephalopathy -- was spread by the practice of feeding the animals ground-up remains of infected animals, turning the herbivores into cannibals to boost their protein consumption. The next year, Holland slaughtered 10 million pigs to contain an epidemic of contagious swine fever that had spread like wildfire through large, densely stocked farms.

It is no wonder that EU consumers are deeply suspicious of such U.S. industrial "pharming" practices as incorporating genetically modified organisms into crops, routine dosing of beef cows with growth-enhancing hormones, and giving prophylactic antibiotics to livestock. But to the United States, eager to market its high-tech foods, such consumer resistance is a nightmare. David Aaron, U.S. undersecretary of commerce for international trade, decried "an atmosphere that can only be described as nearly hysterical concerning food safety in the European Union."

The U.S. beef industry claims that "hysteria" has cost it $200 million a year in lost sales, while limits on genetically modified foods threaten agribusiness with billions in lost research costs and expected profits. In testimony before Congress on June 15, Stuart Eizenstat, undersecretary of state for economic, business and agricultural affairs, predicted, "Within a few years, virtually 100 percent of our agricultural commodity exports will either be genetically modified or mixed with genetically modified products."

Steven Suppan of the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy characterized this prediction as "an iteration of the U.S. policy not to segregate genetically modified products from traditionally produced foods -- consumer choice be damned."

While Europe was still reeling from the Belgian scandal, officials met in Bonn on June 21 for the biannual EU-U.S. summit. Though the trading blocs seemed to be at a standoff, the United States surprisingly gained some ground when European leaders agreed, as one U.S. official noted, "to put science into the discussion."

| "That we have found no proof of danger in the short term does not mean there are no long-term risks." |

After mad cow disease, repeated instances of French blood tainted with HIV and now the dioxin debacle, the EU was hard-pressed to argue that its regulatory system was superior or even safe. USDA Secretary Dan Glickman seized on the dioxin scandal as yet another example of Europe's failure to protect its food supply and as an opportunity to tout the U.S. science-based system as the only rational alternative. "When I chaired the U.S. delegation to the World Food Conference in Rome in 1996," he told the National Press Club on July 13, "I got pelted with genetically modified soybeans by naked protesters. I began to realize the level of opposition and distrust in parts of Europe to biotechnology, [and that it] comes in part from the lack of faith in the EU to assure the safety of their food. They have no independent regulatory agencies like the FDA, USDA or EPA."

Basing food safety decisions on science sounds reasonable -- given the complexity of the issues, the high stakes and the temptation by both sides to disguise protectionist practices as safety issues. But it depends on what you mean by science. "Science is not an absolute matter," says Jan Groenveld, an agricultural counselor with the Dutch embassy. "We in Europe are more concerned about long-term effects. That we have found no proof of danger in the short term does not mean there are no long-term risks."

His position illustrates one of the two competing approaches to consumer protection -- the precautionary principle under which products that could cause serious or irreparable harm must be proven safe before approval. Consumer advocates and environmentalists support this approach, arguing that humans should not be used as guinea pigs.

Industry and much of the U.S. government favor the other approach, so-called "science-based" decision-making. They argue that it is impossible to prove that something is 100 percent safe. Therefore, given the potential benefits to humanity as well as profits to U.S. industry, new products and technologies should be approved unless or until they can be proven dangerous.

The apparent move by EU leaders toward "science-based" decision-making, and away from "hysteria," delighted U.S. Trade Representative Charlene Barshefsky. Speaking of the summit, she noted, "The tone of the discussion on the biotech, hormone and food safety issues was probably the most constructive we have ever had."

A few days earlier, at the G-8 meeting also held in Germany, French President Jacques Chirac nearly soured the mood. He accused the United States and Canada of ignoring public health concerns by attempting to overturn the EU ban on beef from cattle treated with growth hormones and called for a global authority to oversee food safety. But in what Patrick Woodall of Public Citizen calls "a significant compromise" by Europe, the G-8 agreed instead to refer biotechnology disputes to a panel of scientific experts at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a body known to be relatively sympathetic to biotechnology. Woodall predicts that the OECD panel will turn the precautionary principle on its head by making nations prove that biotechnology is dangerous rather than making corporations prove it is safe.

In this new spirit of cooperation, according to the Financial Times, Barshefsky offered "an apparent goodwill gesture," announcing that the United States hoped to substantially narrow its ban on EU pork and poultry imposed after the dioxin scandal. But since the dangers of dioxin are undisputed -- the imported food either contains it or not -- it is hard to imagine what part "goodwill" could play in protecting U.S. consumers. Nor is it easy to understand why, if the USDA was alarmed enough to issue a blanket ban on all European products under its jurisdiction, it neither issued a recall nor tested food on the shelves.

| The combination of industrial farming and globalization created conditions under which accident or misconduct by one small producer had worldwide political, economic and health consequences. |

While the Belgian dioxin scandal may have proven politically opportune for U.S. policy-makers, it may have less happy consequences for consumers. There is no way to assess the quantity of Belgian dioxin that people around the world consumed before the ban and -- in the United States, with its lack of recall -- after it. The chemicals already are pervasive in the environment and the Belgian contaminants simply will be added to the carcinogens already stored in the body fat of all the world's mammals.

Indeed, far more dioxins than were in Belgium's poisoned animal feed routinely enter the environment, mostly from incineration plants. In some cases, contamination continues for years without being noticed. The Belgian contamination, for example, might never have been uncovered if the feed had gone only to cows and pigs. The particular dioxin involved happened to be deadly to chickens and a state veterinarian thought to test for it. In the southeast United States in 1997, the EPA discovered that for years chickens and farm-raised catfish had been eating feed to which dioxin-rich clay had been added as an anti-caking agent. According to reporting by Deborah MacKenzie in the British magazine New Scientist, the FDA eventually banned the feed -- but allowed moderately contaminated chickens to be sold as food, as long as most of the fat was removed. While levels in the U.S. samples -- at least at the time they were discovered -- were lower than in the Belgian feed, the contamination had a longer time to accumulate in consumers.

In the end, the Belgian incident was extraordinary not for the quantity of dioxin involved but for the way it spread so quickly around the world. The combination of industrial farming and globalization created conditions under which accident or misconduct by one small producer had worldwide political, economic and health consequences.

The use of this crisis by the United States to score trade points while risking consumer health should give Europeans pause as they consider putting their trust in a U.S.-type regulatory system and its commitment to "science."

|