Iraq: Life in the Shadow of War

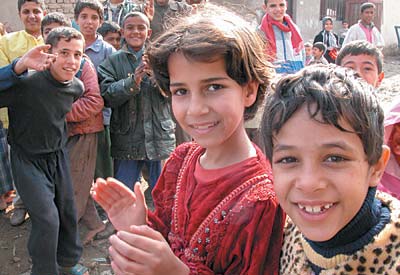

The faces and voices of the victims of war and human rights abuses. BAGHDAD, IRAQ The air is thick with the sense that real life will resume only after sanctions, bombings, and the threat of invasion finally end. In late January, as war lumbers ever closer, wedding parties still dance; cars and commerce fill the streets, artists perform and create. But the infrastructure of this once prosperous and educated country is in ruins, and most Iraqis survive on the most tenuous and miserly terms. Medicine, electricity, and clean water are in short supply; U.S. bombs rain down both inside and outside the no-fly zones. If people blame Saddam Hussein for their misery, they are not eager to share that dangerous sentiment with a stranger, much less discuss the terrible state of human rights. The closest anyone came was a man who quietly volunteered: "Whether I hate Saddam or not, and I'm not saying I do, I hate America the government, not the people for what it did and is going to do to our children." Among the people I met, those feelings were paramount: concern for Iraq's children and a careful differentiation between the American people and their government. As the Bush administration prepares for war, Iraqis are trapped in an amber of waiting. They look to the future with a mix of fear and fatalism that Americans began to comprehend after 9/11. Iraqis know that if a major attack comes, many of their loved ones and neighbors will suffer. Some will die quickly from a bomb or a bullet; some, felled by poverty and disease, will expire slowly like a fire in the rain; amd some will live on, as before, in the shadow of loss.

If his plant's capacity is further damaged by an attack, Kassam says, hospitals, schools, and families will have to turn to the polluted Tigris River that runs through Baghdad. Told about legal efforts (led by the New York-based Center for Constitutional Rights) to show that military attacks that "disproportionately" impact civilians are war crimes, Kassam responds politely. "I appreciate the attention of those lawyers, but the U.S. administration is cruel. If they knew anything about human rights it would not have happened." As he speaks, Kassam's eyes flick to a photo on the wall of a baby girl. "I live inside the facility with my family, and the first who benefit when I do my job are my children." I ask what happened to his family during the war, and he says he doesn't want to talk about it. Outside the office, Kassam is standing alone. I ask him again if he can tell me about what happened to his family. He stares quietly across a filtration pool. Then, he talks about 1992 when the war had been over for a year and Iraq's water treatment facilities and its bombed electric grid remained crippled. "Miriam was my first baby. She contracted diarrhea." I ask if it was a water- borne illness, and he nods. "We couldn't find medicine. I stayed with her for 42 days. We lost her, and we have lost so many other children in Iraq." About the prospect for war, he says, "My anger has no limits. I am angry at those who carry out war against innocents. I cannot say more."

"I was at work on Dec. 1," says Faiyad. "I am an accountant and good with numbers. I was at South Oil Company and was carrying paperwork to my office when I heard thunder, a huge sound, and something hit my leg, and I was thrown into the air." Under her scarf, Faiyad's head is wrapped in bandages; a metal apparatus, like a TV antenna tuned to pain, protrudes through dressings on her leg. According to international news reports, it was a U.S. bomb that fell on her workplace. Faiyad says that the facility was strictly civilian and that the attack killed one and wounded eight. "Now when I hear planes I am so afraid," says Faiyad, adding softly, "afraid I will never walk again. Who do I blame? I blame the American government, but also the people. It is not too hard for Americans to listen to the news and learn the truth and to educate the ignorant ones who want to make war on us."

The effect, says another doctor, is that "people die. Some of the female doctors cry when we know what to do to save a life and we just can't do it." We walk to a pediatric ward with 10 metal frame beds. Clean and spare, it has none of the high- tech bedside equipment common in a Western hospital. A relative sits by each child, stroking a brow or holding a hand, or with the sickest, just watching. At the end of the room a 10-year-old girl lies motionless with half-open unblinking eyes. She has been sick for years, says her father through a translator and adds, in all the English he can muster, "I am tired of the illness, of the sanctions. Look at my daughter, please. Her name is Zahara. It means flower. But now she is shut."

Terry J. Allen, a veteran reporter, is editor of Amnesty Now. She went to Iraq in January in a private capacity as part of a research mission organized by the Center for Economic and Social Rights (CESR) and interviewed ordinary Iraqis in homes, workplaces, hospitals and on the street, usually through Jordanian translators hired in Amman by CESR. In most cases Iraqi "minders" were not present. She also was briefed by Iraqi and U.N. officials. The trip had no connection to Amnesty International; the views presented here are her own. |

|---|